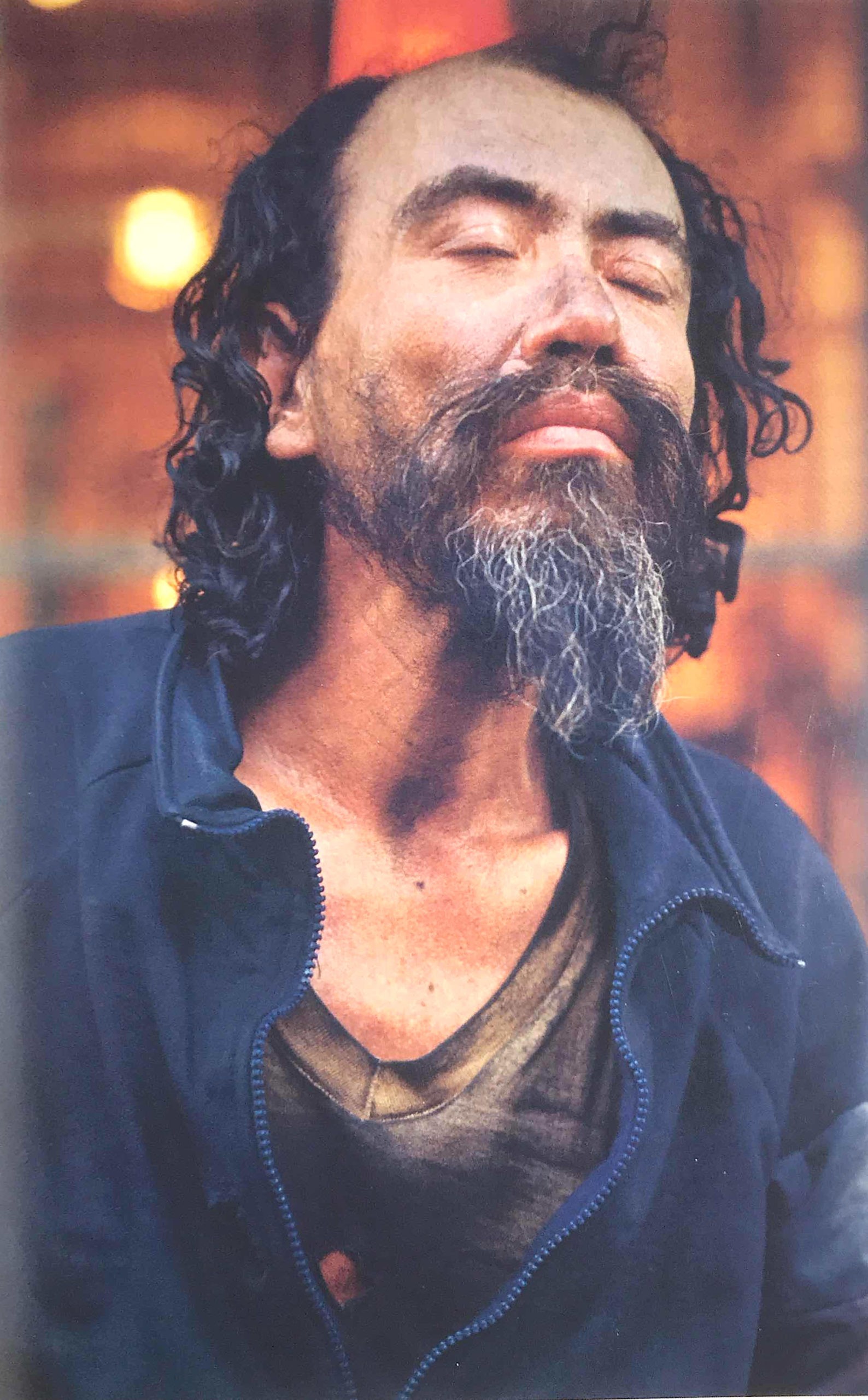

The photo shown here was taken by artist Robert Bergman and published in his book A Kind of Rapture, which documents the people he met on the street during his travels across the United States. Like Bergman, I have spent a large portion of my career working in underserved communities. Although I would not consider myself an expert on homelessness, I have had more first-hand interactions and know more about the subject than the average person.

Recent statistics reveal a disturbing but not surprising increase in homelessness over the past four years. As many have seen their wealth balloon, our nation’s homeless population grew by about 2 percent per year. The government estimates that more than 106,000 children are among the homeless, and 11,000 of those children live outside or on the streets. African Americans make up a disproportionate 30 percent of the homeless population, and Latinos make up 23 percent. Homelessness is a complicated, multi-faceted issue. Those who have never interacted with them often form wildly inaccurate ideas about their character and value to society.

One of my first interactions involved offering a sandwich to a homeless man in the park, which resulted in an enlightening conversation. He was reading a Greek classic by Homer, which he had checked out from the local public library. He was intelligent and articulate. He explained he had a disability that made it very difficult for him to hold down a typical job and preferred to be called a hobo. He traveled regularly between several states by hopping on trains, picking up assistance checks, and tracking favorable weather. He had a dignity and sophistication that surprised me. I was glad to help him, but I did not pity him. In fact there was a part of me that envied his freedom.

Since this encounter I have had numerous similar experiences. I have seen cardboard street shelters that are cleaner and better organized than my children’s bedrooms. My closest friend on Bainbridge Island—an affluent community across the water from Seattle—was a homeless gentleman living in his van, which he parked across the street from our home. Without trading in carbon offsets, the average homeless person has a negative carbon footprint— living off the waste and excess of our insatiable consumer economy.

Based on these experiences, I no longer see the absence of a typical “home” as a problem. Rather, what is so disturbing, and should disturb everyone, is the indignity these fellow human beings are forced to endure. Many of these individuals can’t take care of themselves due to drug addiction or mental illness, they don’t have families or friends who can intervene, and they need our collective and sustained assistance. Others need a place to get basic health services and facilities to clean and care for their bodies. Some need a warm meal, a smile, some encouragement, an opportunity and, like all of us, occasionally need to be confronted and held accountable. However, to muster the will to resolve this disturbing situation, we must first recognize these human beings as valuable members of our community.