My dad, like approximately 4.5 percent of the general population, suffered from color blindness— the inability to see red, green or blue. My father could not distinguish the color blue. Being an artist who has spent countless hours mixing paints, I occasionally wonder if we all suffer from some form of color blindness. Our modern computers can display up to 16.5 million colors, many of which our eyes cannot distinguish. Our eyes are limited and can only detect electromagnetic radiation waves between 390 to 700 nanometers — a fraction of the overall spectrum. However, even within the visual light spectrum there are infinite colors, many of which our eyes have never seen.

Although we know an infinite number of colors exist, to reproduce them in the real world we have to develop stable pigments from the elements found in the natural environment. This is not as easy as one might think. For example, creating a pigment may involve harvesting and pulverizing bug parts.

It is estimated that pigments are a $30 billion industry, and unfortunately, many pigments are made from toxic substances. Bright red may be the worse culprit in this regard. It is made with cadmium — an element that sits at 70 on the list of 275 chemicals on the U.S. Toxic Substance and Disease Registry. For several decades red colored Legos contained cadmium, a proven carcinogen. The European Union considered banning cadmium red pigments, but artists groups successfully thwarted the effort. There currently is no viable alternative to produce a stable, non-toxic bright red pigment.

Black is another interesting color to consider. Of course pure black is in fact the absence of light and therefore the absences of color. However, black pigments are not pure and therefore contain subtle colors and hues. The works displayed at the Rothko Chapel in Houston, Texas, are a great example of this phenomenon. The paintings created by renowned artist Mark Rothko before his death appear at first to be large black canvases, but as your eyes adjust, the rich hues and shades of different blacks come into focus. The blackest black is Vantablack, which was developed recently by a UK-based company Surrey Nanosystems. Vantablack absorbs over 99.9 percent of the light that hits its surface. It is so black that even three-dimensional objects painted with it appear as flat silhouettes to the eye. Immediately sensing an opportunity Anish Kapoor, a celebrated British artist, brokered an exclusive arrangement with Surrey Nanosystems to explore the artistic applications for Vantablack. This infuriated many artists, who felt that others should be allowed to experiment with the new coating.

In 2009 Mas Subramanian, a material scientist at Oregon State University, developed a new pigment of blue called YInMn Blue. To put this into perspective, YInMn Blue was the first blue pigment developed in more than 200 years. He accomplished this feat accidently when his assistant mixed some obscure chemical elements and heated them up to 2200 degrees Fahrenheit for 12 hours, and out popped YlnMn. The blue is astonishingly vibrant and unlike any other type of blue you have seen. It is also stable and non-toxic to humans. Astonishingly, when this new pigment is mixed in paint and placed on a roof, the spaces underneath remain 55 degrees cooler than ones coated with a cobalt blue.

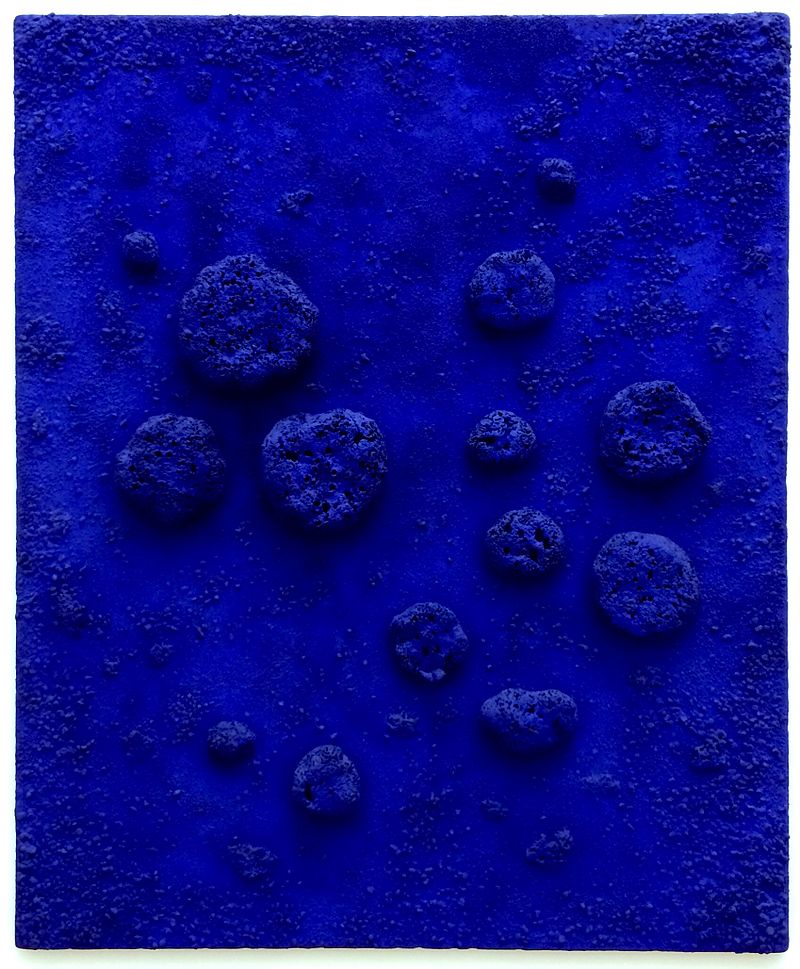

French artist Yves Klein is well known for developing his own vibrant blue paint, which eventually became the focus of his work and defined his artistic career. Not many artists have developed their very own color, but Yves developed International Klein Blue (IKB) in collaboration with a paint supplier in Paris. The paint gets its unique appearance from a synthetic resin binder that suspends the ultramarine blue pigment in a way that enhances its vibrancy. One of his sponge paintings is shown here. It was not until 1958 that Klein made this color the main feature of his work — effectively turning his art into a mesmerizing experience using a single color … BLUE. A compelling body of work my dad and countless other will never be able to fully appreciate.

This reminds me of another pigment that always comes to mind when I think of paint, “Mummy Brown.” Supposedly made of ground up mummified corpses, artists would hire tomb/grave robbers to retrieve these mummies to obtain this specific hue of brown. It is incredibly macabre to think that there are paintings that have human remains, thousands of years old on them, out there. Fascinating nonetheless. Makes me realize perhaps there are more reasons an artist chooses a specific paint aside from color…

Thanks for the information. I had not heard of this and did a little research – very interesting.