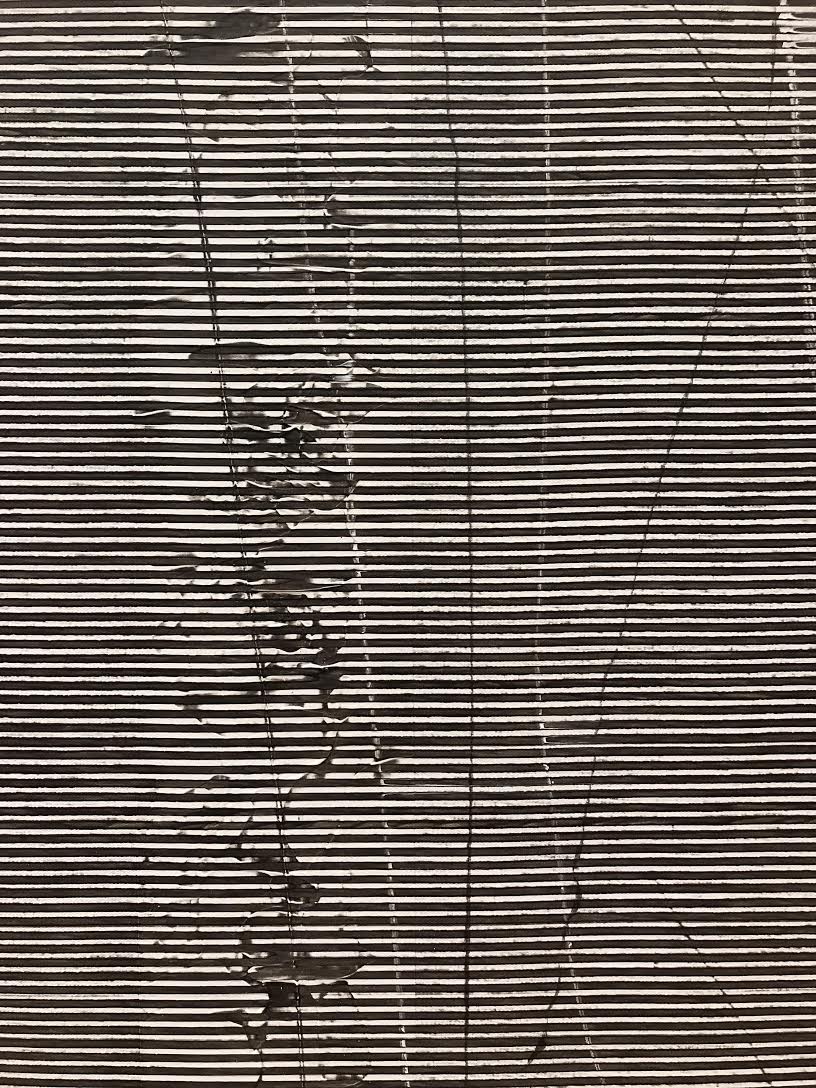

The image here shows a portion of an acrylic painting by American artist Jack Whitten entitled Yiota Group II. In this particular work Whitten uses a tool he calls a “developer” that he drags across the canvas, removing a layer of paint and revealing the dark surface beneath.

In earlier paintings his developer was an Afro comb. In his later work the developer evolved into a notched piece of galvanized sheet metal. The metal sheet was pulled across the entire canvas in a single continuous movement that lasted about three seconds. As if this instrument was an enormous pencil, Whitten considered the work to be a single line.

Most of us consider the line a device to convey something else. We rarely consider the line itself as the culmination of our effort. The canvas is quite large, so if you get close enough it can envelop your entire cone of vision. Standing in front of this painting is like examining a line through a powerful microscope. It is like being shrunk and allowed to leap onto the line itself. However, what is most mesmerizing about this work is not the precision or regularity of the horizontal striations but rather the disruptions to the pattern.

The seeming imperfections become the object of one’s interest.

This is a common compositional strategy, in which a standard condition or datum is established, and as a result variations or disruptions to that condition create visual interest. Consider what would happen if the disruptions increased and began to dominate the majority of the canvas. There is a tipping point when the horizontal striations would become the interest. Having explored this phenomenon extensively, the amount of variation seems to be inversely proportional to the interest it creates. For example, a small stain that appears on a blouse can garner more focused attention than a completely soiled piece of clothing.