Spatial perception has been a human fascination for centuries and has become a distinct and important area of research within the field of psychology. The reason is that the most important questions being asked today regarding our perception centers around the relationship between the mind and the body. How exactly do we become aware of the relative position of our bodies and objects within our environment?

In the 18th century George Berkeley suggested that the way the eye receives visual information — as two-dimensional retinal images — necessitates that spatial understanding be developed through learned experience. How else could one identify a cube that has six sides if only three of the sides are visible at any given moment? Visual artists, like myself, are students of spatial perception and are interested in how we organize objects in space through movement, form, color and their interactions.

At a basic level our ability to accurately perceive space as it corresponds to physical reality is essential to our survival. Can you imagine eating a meal or driving a car without this ability? However, many of the ways we process spatial information can be utilized to confuse, disorient or challenge our perception.

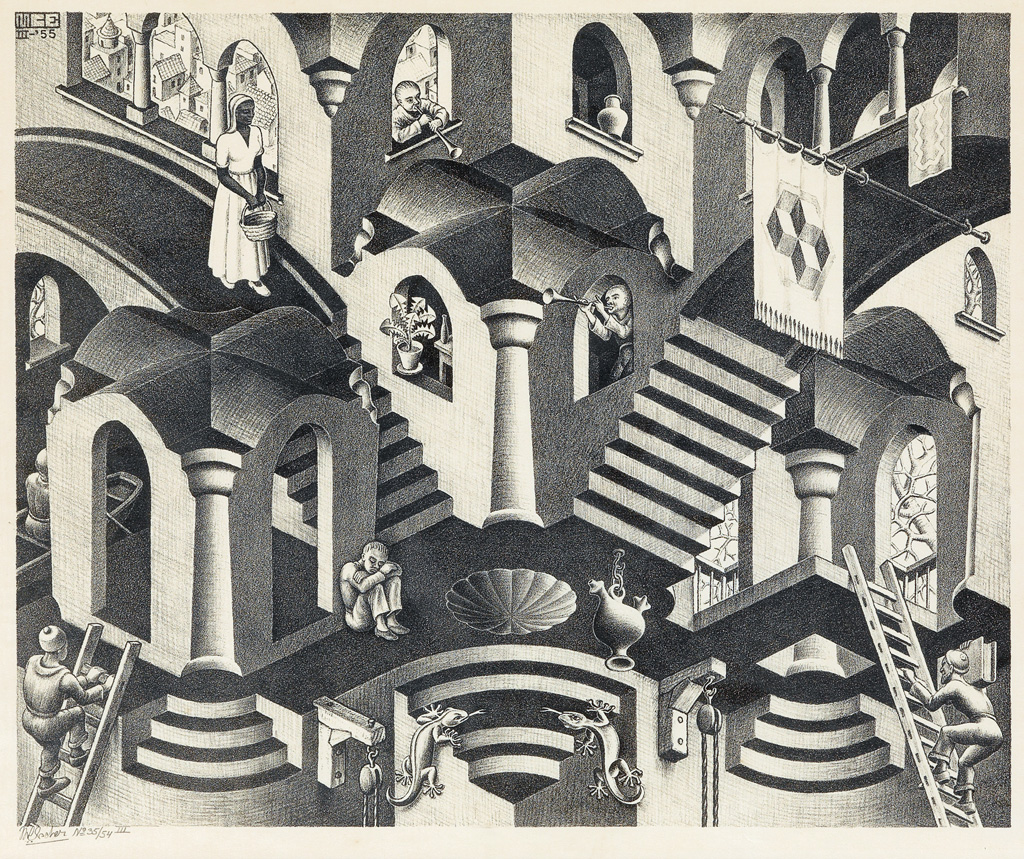

M.C. Escher exploited the way our brains process visual information to produce this 1953 work entitled Multiple view points and impossible stairs. This is just one of his etchings that utilized principles of visual perception, perspective drawing and geometry to depict impossible objects and environments.

Today we recognize that there is much more to spatial perception than simply using our eyes. We use all our senses in coordination in order to process spatial information, including our often-overlooked sense of balance. Individuals that are blind at birth, for example, can develop sophisticated spatial understanding largely through touch and sound.